Jeff Corwin PhotoThe Anthropology of GarbageLecturer Jason De Leon explores modern migrationStory by Jeff Bond

Photos by Jeff CorwinThe toddler's scuffed white shoe bears the words of an anguished loved one far away.

"I'm going to miss you" is penned in Spanish in one place, "I'm going to miss your kisses" is written in another. "Please don't go."

Who owned the discarded shoe and who wrote the words of love may never be known. It was found last summer in the Arizona desert by Dr. Jason De Leon, UW full-time lecturer in anthropology, at a "lay up" site—a shaded resting place used by migrants illegally crossing the border.

The shoe is one of hundreds, if not thousands, of discarded items De Leon has collected at sites around the Mexican border in his work to better understand one of the world's largest ongoing modern-day migrations—the exodus of millions of Latinos into the United States.

It is estimated that more than half a million immigrants attempt to cross the border in southern Arizona each year. This controversial migration movement has become one of America's great political flashpoints, dividing communities and political parties. But while this phenomenon is often debated and argued about, the process of migration has attracted little rigorous academic attention.

That is something De Leon hopes to change through his Undocumented Migration Project (UMP). Launched in November of 2009 at the UW, the UMP uses the disciplines of ethnography and archaeology to better understand the complex social, political and economic systems that revolve around the undocumented migration movement.A boot recovered by De Leon in the desert around the U.S.-Mexico border.

Jeff Corwin PhotoAn economic anthropologist and a trained archaeologist, De Leon has conducted archaeological and ethnographic research in the U.S., as well as in Mexico and Panama. The child of two immigrants, De Leon, 33, has been interested in the migration movement for as long as he can remember. But it was during the last decade that he became close with many migrants while working on archaeological digs in Mexico. Friends also introduced De Leon to resting sites used by migrants in the Arizona desert, an experience that deeply impacted his outlook on these individuals and the hardships they face.

After talking with other archaeologists, De Leon decided to combine archaeological and cultural studies of the migrant movement in a way that hadn't been done before to better understand this ongoing phenomenon.

Using archaeology, De Leon studies clothing and other discarded items to determine how many people are crossing the desert, where they came from, and their migration habits. Take, for instance, backpacks. De Leon has collected hundreds of backpacks and, through interviews, is aware that almost everyone old enough to carry a backpack wears one on the trek. He expects to use the number of backpacks he finds to estimate the number of people stopping at the lay-ups.

While backpacks may be universal, the shoes left behind help De Leon and the UMP team determine the age and gender of the migrants. Random samples of dated items, such as water bottles and food containers, help identify where and when the migrants bought the items, giving researchers a timeline for their movements and a sense of the path they may have taken from Mexico to the rest area.

The enthnographic aspect of the project involves researching the migrant experience on the Mexican side of the border, including talking with recent deportees about their experiences and their activities in the U.S. By combining the archaeological finds in the Arizona desert with the ethnographic data collected on the Mexican side of the border, De Leon can determine where migrants originate from, why they make the journey, what dangers they face and how the migration movement is altering the Mexican culture and economy both along the U.S. border and even farther south in Mexico. And, he's developing a more honest picture of this experience and adding a human dimension to the issue of undocumented immigration.A framed picture of a Catholic saint found by De Leon.

Jeff Corwin Photo"One of my goals for this project is to help everyone understand what is going on at the individual level during this border-crossing experience," De Leon says. "There is so much myth, even among migrants themselves, about what happens when crossing the border and then walking through the desert that I think it takes someone from the outside to take a fresh look at the big picture." Such work has won De Leon praise from his colleagues who share his interest in Latin American Studies at the University of Washington. "When you see a pair of baby shoes left in the desert, it changes your perspective about who these people are and what crossing through the desert must have been like," says Dr. José Antonio Lucero, a professor of political science at the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies. "The power of these objects makes this issue more human and real."

Dusting Off Archaeology

De Leon is well aware of archaeology's reputation as a dusty science with little usefulness in today's world. Changing that attitude is another of his motivations. Using archaeological methods in studying the resting sites will train UMP students in the art of archaeology and, he hopes, help prove the science's ongoing relevance.

"One of the biggest problems that we, as archaeologists, have is often times selling ourselves as being relevant to the general public," De Leon says. "I believe archaeology is extremely relevant. We can help society learn about history's past mistakes, we can help gauge long-term impacts on the environment and how things change over time. But I also think that archaeology can be useful for understanding modern-day phenomenona, such as the undocumented border crossings, an important issue that is very hard to get information about."

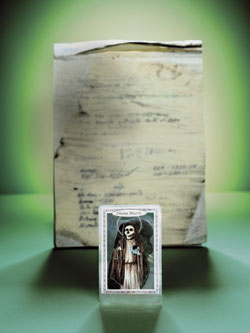

In a small, cluttered office in Denny Hall, De Leon is surrounded by recovered artifacts he has collected to help reconstruct the lives of these migrants. His shelves hold a collection of plastic water jugs, and everywhere are boxes full of backpacks, clothing, personal photographs, birth certificates and even the notebook of a smuggler, or "coyote," complete with names and phone numbers. It is what he refers to as the "archaeology of the contemporary."A "coyote's" notebook and a Santa Muerte card recovered by De Leon.

Jeff Corwin PhotoDe Leon says he never ceases to be surprised or moved by the things he uncovers at the hundreds of sites he has visited, places where migrants gather to rest and sleep during the heat of the day as they navigate their way through the horrors of the Mexican border, through the dangers of the desert, and past border patrol to make their way into America.

"Just the mass of items at the site is very, very overwhelming for me," De Leon says. "No matter how many times I've seen these sites, I've never really become desensitized to it."

The Artifacts of an Exodus

Funded with about $52,000 in grants from the University of Washington's Royalty Research Fund and the National Science Foundation's RAPID Grant program, De Leon's UMP team—consisting of one graduate student and four undergraduate students—began its initial work in the summer of 2009.

The team focused its archaeological work in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Reserve, an area in southern Arizona located just north of the village of Sasabe along the Mexican border. The bulk of the migrant interviews and the study of the economy and culture of this movement were done in and around the town of Altar, in Mexico, and the border city of Nogales, Ariz., home to a 10-foot-high, mile-long steel barrier and the main repatriation point for undocumented migrants caught on the U.S. side of the border.

From an archaeological standpoint, the project team treated the lay-up sites just as they would any site holding ancient artifacts. Using Global Positioning System technology, they mapped the site's coordinates, drew a grid and estimated the site's area. Then, to get an idea of how the site was used, they searched the site for "discrete activity areas," which include food preparation and sleeping locations. The team examined and collected artifacts, such as clothing, backpacks and water bottles that would yield clues about the migrant groups that use the spot, including how many people were in the groups and the number of men, women and children at the site.A gated community 200 feet from an Arizona lay-up site.

Jeff Corwin PhotoThey also plan to study the sites over time to see if the number of migrants at the sites changes for evidence on whether the number of migrants crossing the border is increasing or decreasing. While De Leon doesn't have enough data yet to make any firm conclusions, he has noticed that the larger sites he visits are considerably older, while sites with more recent activity appear to be sheltering smaller groups. They also tend to be located in more remote and dangerous areas. This, he theorizes, is due to increased border security and a more sophisticated apprehension system developed by border patrols.

De Leon says the slower economy may also be playing a minor role in reducing the number of migrants estimated to be visiting such sites, though many of the people he spoke to in Mexico last summer weren't even aware the U.S. was in a recession.

As for the large amount of clothing found at the lay-ups, De Leon says one theory is that the clothes are discarded when the migrants clean themselves up after the arduous trip through the desert and change into clean outfits before walking into town or being picked up by smugglers.

Documenting the Undocumented

De Leon has also spent a lot of time in Mexico developing friendships and contacts among the migrant population in order to better understand their experiences. Last summer De Leon interviewed Mexican nationals who had gathered in border communities such as Altar and Nogales to plan their trips into the U.S. The aim was to record the experiences of migrants and to document the resulting impact on the area's economic infrastructure.

Overwhelmingly, illegal border crossing in this region continues to be a Mexican phenomenon, with Mexican nationals comprising about 90 percent of those planning to cross the border and people from Central and South America making up the remaining 10 percent. There are also reports some Lebanese and Chinese nationals have been smuggled across.A burlap-covered water bottle found by

De Leon.Jeff Corwin PhotoDe Leon found that a considerable part of the region's economy now relies on outfitting and preparing migrants for their journey across the border. The Mexican town of Altar, located southwest of Nogales, boasts stalls full of backpacks, camouflage clothing and other items needed for the border journey. Local convenience stores stock shelf upon shelf with electrolyte drinks and plastic jugs of water.

In the border region around Nogales, De Leon built up such a rapport with some of the migrants that he convinced them to carry disposable cameras across the border and leave them at pre-arranged locations. The idea was to have the migrants take pictures of the things they thought were most important to them when crossing the border.

What surprised De Leon was the level of violence some of the migrants experience on their journey. In interviews, De Leon learned that migrants are sometimes beaten, robbed or even kidnapped and held for ransom by border bandits, and that women are often raped. Migrants must also avoid drug smugglers, who could deter them from crossing the border or kill them. Even if they successfully avoid these dangers, their "coyotes" may abandon them in the wilderness.

De Leon also found many migrants who had tried to cross the border repeatedly, only to be caught each time and repatriated to the Mexican government.

"These are the people you see sleeping in the cemetery," De Leon says. Virtual prisoners in border communities, these migrants have no money or energy to get home and often are too traumatized to attempt yet another border crossing. And still, as bad as these border communities and crossings are, the home they have to return to is often times even worse.

Putting Archaeology on the Cutting Edge

Having recorded more than 45 hours of interviews, and logged at least another 200, and collected more than 150 pairs of shoes, 2009 was a whirlwind year for De Leon and his fledgling UMP. And the scientific world is taking notice of his unconventional research.

"His is one of the most cutting-edge uses of archaeology anyone has seen in the last decade," says Ran Boytner, director for international research at UCLA's Costen Institute of Archaeology.Photo by Michael WellsThis summer, De Leon plans to begin a multiseason archaeological analysis of certain lay-up sites that are located in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Reserve. Eventually, he hopes to expand the research into other parts of Arizona, California and Texas. He also hopes to begin working with Mexican colleges and universities on the study of Latino migration into the United States.

He is even talking with his wife, Abigail Bigham, a senior fellow in the Division of Genetic Medicine and Pediatrics at the UW, about adding a biological aspect to the research and using DNA to help with the identification of remains found in the desert.

De Leon chuckles as he reflects on how what began as a relatively simple idea of studying the archaeological aspect of the migrant movement continues to morph into an ever-larger project.

"In the beginning, people looked at me like I was crazy," De Leon says, shaking his head. Now, he's getting calls from the Smithsonian.

—Jeff Bond, '88, is a Seattle-based freelancer who writes about business, culture and politics in the Puget Sound region.

DANCING NEBULA

When the gods dance...

Sunday, September 25, 2011

The Anthropology of Garbage

via washington.edu

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment